Pondicherry: Ocean Winds, Tides & Currents

Notes & reflections from 'Know your Bioregion' session by Aurofilio - organised by Aurovanam at the Pondy Yacht Club

As someone who was born on the East Coast, close to the beach in Visakhapatnam, and now lives further south in Auroville near Pondicherry, I’ve always been fascinated by the oceans — that vast, blue expanse inviting, intriguing and more often than not inaccessible for most to venture into. So when I heard about this session by Aurofilio (or Filio, as he’s fondly known), I signed up immediately. A visit to the Pondicherry Yacht Club had been on my list for a while, but life kept throwing surprises each time I tried. This Saturday was no different — but I was determined not to miss this precious opportunity to deepen my connection with, and learn more about, the bioregion I now call home.

Filio who was born in Auroville and grew up in Pondicherry, is a living library in matters of the Ocean and Coastal health. With a master’s degree in coastal management from Newcastle University, he came back home to eroding beaches and has seen and shaped the shifts this stretch of precious coastline has undergone, playing a key role in its restoration and conservation with his deep knowledge and committed efforts. His work along with the team at PondyCAN has directly impacted how Pondicherry’s coastline looks today, his passion for protecting this environment is both inspiring and the work essential to take note of for all of us living in this bioregion.

A bioregion is not just a stretch of land or a political boundary—it’s a living system, defined by natural features: the rivers, coastlines, mountains, plants, and weather patterns that give a place its unique character. And importantly, a bioregion includes the all beings, the people who live there, shaping and being shaped by the land, seas and invisible winds.

The session opened with an introduction, followed by Filio recounting how he and his family first discovered this stretch of land 24 years ago, drawn by their love for water sports. He reminisced about how it used to be a quiet, hidden spot known only to a few. With time they noticed that pollution was growing steadily and garbage was piling in, so they chose to open up the space and make it a communal centre for water experiences - sailing, kayaking etc. For a while it was a hidden gem until in the last couple of years they saw eco-tourism surging. Mangrove boating became popular, with flyers across town promoting the experience. Today in this neighbourhood, more than 60 boats operate daily—up from just a handful a few years ago.

The peace they once enjoyed is gone, but Filio sees value in the change. With tourism came a growing awareness that protecting the mangroves is key to sustaining local livelihoods. “Yes, increased footfall has its own impact. But we believe it’s better than the alternative—neglect, pollution, destruction.” he says with a warm smile as a gentle wind comes along on this journey.

Expanding the conversation beyond the immediate surroundings, Filio spoke about the islands of Pondicherry, the rivers flowing through the bioregion, and historical trade routes. These wetlands, he explained, were once part of a vibrant network of waterways connecting Pondicherry to the sea. Over time, with both natural shifts and human interventions—especially dam building for agriculture during the 18th and 19th centuries—many of these rivers were cut off from the ocean, slowly drying up and losing their connection to the rich past.

Today, much of the region’s stormwater runoff—particularly from the Grand Canal—ends up in these backwaters, carrying with it urban waste. These delicate wetlands now bear the environmental burden of pollution from a growing city.

After grounding us in the geography and hidden history of our bioregion, Filio reminded us that Pondicherry isn’t just what we see on land—it’s also the vast, living landscape offshore, a critical part of our ecological and cultural heritage. From there, he shifted gears into tides, winds, and currents, opening a window into the dynamics of the oceans and its impact on the bioregion.

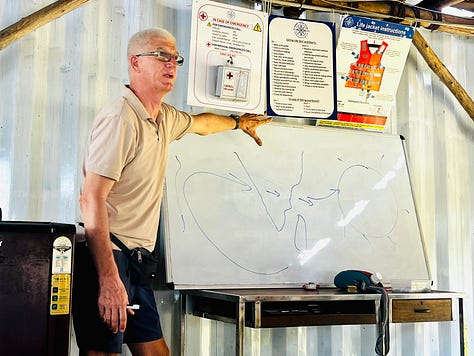

Being a coastal town, the ocean shapes almost everything here—from the winds, to the moisture in the air, to the currents, to the waves, and even the shape of the shoreline itself. And all of that power ultimately come from the Sun. He explained how the tides, the waves, the winds—all of it—starts with the sun and how its energy drives everything we experience here on the coast. He then explained, how the ocean breathes, why the water moves in and out, gravitational forces of the Moon and the Sun and how the phases on the moon influence tides. He gave us answers to the different kinds of tides - spring tide, neap tide - we get two spring tides and two neap tides every month, and every day we experience two high tides and two low tides and the tides shifts by about 45 minutes daily as determined by the moonrise. While we have semi diurnal tides here in Pondy, he also explained how not every place on Earth has the same rhythm, there is also diurnal tides & mixed tides. We learnt about tidal range and that tides aren’t controlled only by the Sun and the Moon and that scientists have identified over a hundred factors—called harmonic constants—that influence tides. With the whiteboard and marker in hand, he made the concepts clear and comprehensive for everyone present.

From tides, Filio took us on a journey to understand Winds and the Monsoon patterns in the South East with attention to our bioregional rainfall patterns and the role of the Western Ghats. Wind is part of a giant, beautiful dance between the land, the sea, the sun, and the seasons. It is invisible but wind is a constant companion, shaping everything around us in ways we often overlook. We learnt about winds, currents and the seas movements. Winds don’t just push ships—they push water, too. When wind blows steadily over the ocean, it creates currents—like rivers flowing in the sea. These currents help distribute heat across the planet, support marine life, and even influence our climate. Almost all waves we see in the ocean are created by wind. Local winds create short, choppy waves, while distant storms generate long, rolling waves called swells. These swells can travel for thousands of kilometers, neatly lining up like soldiers by the time they reach our beaches. Surfers love them because these waves are powerful and beautifully formed.

And waves don’t just stop at the beach—they shape the land. Over thousands of years, waves, combined with rivers and wind, have sculpted India’s distinctive V-shaped coastline. It’s a system always searching for equilibrium. The problem is, we’ve disturbed that balance. It might all seem obvious and stuff one heard, read or came across before, but when an expert like Filio speaks about it in context, one realises how much we take for granted about the natural phenomenon and patterns that influence our being.

Taking Pondicherry as an example he helped us understand how, before the harbour was built, sand flowed naturally along the coast, replenishing beaches as it went. But after construction, that flow was blocked. Beaches on one side grew, while others simply vanished. It’s not just harbors. Dams on rivers stop sand from reaching the sea, and sand mining for construction reduces it even further. Without that constant replenishment, the sea begins to eat away at the land. It’s like a broken machine. The natural system was always dynamic but stable. Now, we’ve jammed the gears, and the whole machine is off-balance. There has been enormous efforts to restore our beaches but unless we maintain those efforts, nature won’t simply “fix itself.” he added. The winds, the waves, the currents, the sand—they’re all part of a giant, interconnected system. It is beautiful. And it is fragile.

As Filio was concluding his crisp sharing of years of applied experiential knowledge, the boat that was to take us on a short trip into the young neighbouring mangroves parked up at the jetty just outside joining the parked kayaks and sailboats. With our life jackets on, we climbed aboard one by one, drifting past rows of fishing boats and the buzzing tourist carriers Filio had spoken about earlier. He oriented us and shared more about these waterways and how it was possible to kayak or paddle on these waters just a few years ago before it got as busy as it is today.

Brushing past the young mangroves was a beautiful experience —gentle, tender green against the dark greyish green of the polluted water we were floating on. There are seven species here, with two dominant ones—silver-leaved and red-rooted varieties—Filio explained as he showed them to us, answering Lochan’s curious inquiry about the different trees absorbing nutrients from the city’s runoff. We moved through narrow openings and back again, with our boatsman from the nearby fishing village navigating the shallow waters with care. Every question we had was met with an answer, and we got to experience one of the hidden jewels of our bioregion from the eyes of someone who has a deep rooting with it.

Eventually, we travelled toward the estuary, where backwaters merge with the salty expanse of the ocean, before looping back to where we had started. While the steady pace of the boat, the gentle wind, and the vibrant green were a treat to the senses, the sharp smell of fuel in the air and the floating garbage amongst the resting crabs on the mangrove roots was a sobering reminder of the other side of it all.

As we stepped off the boat, Filio pointed out how the tide had shifted since we began, tape measure in hand—making visible the subtle changes that usually go unnoticed, bringing us one step closer to observing the forces constantly shaping the world around us. We made our way back to land, welcomed by a delicious glass of fresh mango juice and more conversations before heading home equipped with essential nuggets of knowledge and fun facts about this living and ever changing bioregion we call home.

Now, each time the sea breeze brushes against my skin, I carry with me a bit more curiosity about its journey — with more attention, more gratitude, and a deeper understanding of the ocean’s constant, delicate dance towards balance.

A bioregion is not just a stretch of land or a political boundary—it’s a living system, defined by natural features: the rivers, coastlines, mountains, plants, and weather patterns that give a place its unique character. And importantly, a bioregion includes the people who live there, shaping and being shaped by that land and sea.

The session opened with an introduction, followed by Filio recounting how he and his family first discovered this stretch of land 24 years ago, drawn by their love for water sports. He reminisced about how it used to be a quiet, hidden spot known only to a few with pollution growing steadily. And in recent years, eco-tourism has surged. Mangrove boating became popular, with flyers across town promoting the experience. Today, more than 60 boats operate here daily—up from just a handful a few years ago.

The peace they once enjoyed is gone, but Filio sees value in the change. With tourism has come a growing awareness that protecting the mangroves is key to sustaining local livelihoods. “Yes, increased footfall has its own impact. But we believe it’s better than the alternative—neglect, pollution, destruction.” he says with a warm smile as a gentle wind comes along on this journey.

Expanding the conversation beyond the immediate surroundings, Filio spoke about the islands of Pondicherry, the rivers flowing through the bioregion, and historical trade routes. These wetlands, he explained, were once part of a vibrant network of waterways connecting Pondicherry to the sea. Over time, with both natural shifts and human interventions—especially dam building for agriculture during the 18th and 19th centuries—many of these rivers were cut off from the ocean, slowly drying up and losing their connection to the rich past.

Today, much of the region’s stormwater runoff—particularly from the Grand Canal—ends up in these backwaters, carrying with it urban waste. These delicate wetlands now bear the environmental burden of pollution from a growing city.

After grounding us in the geography and hidden history of the region, Filio reminded us that Pondicherry isn’t just what we see on land—it’s also the vast, living landscape offshore, part of our ecological and cultural heritage. From there, he shifted gears into tides, winds, and currents, opening a window into the dynamics of the oceans and its impact on the bioregion.

Being a coastal town, the ocean shapes almost everything here—from the winds, to the moisture in the air, to the currents, to the waves, and even the shape of the shoreline itself. And all of that power ultimately come from the Sun. He explained how the tides, the waves, the winds—all of it—starts with the sun and how its energy drives everything we experience here on the coast. He then explained, how the ocean breathes, why the water moves in and out, gravitational forces of the Moon and the Sun and how the phases on the moon influence tides. He gave us answers to the different kinds of tides - spring tide, neap tide - we get two spring tides and two neap tides every month, and every day we experience two high tides and two low tides and the tides shifts by about 45 minutes daily as determined by the moonrise. While we have semi diurnal tides here in Pondy, he also explained how not every place on Earth has the same rhythm, there is also diurnal tides & mixed tides. We learnt about tidal range and that tides aren’t controlled only by the Sun and the Moon and that scientists have identified over a hundred factors—called harmonic constants—that influence tides.

From tides, Filio took us on a journey to understand Winds and the Monsoon patterns in the South with attention to our bioregional rainfall patterns. Wind is part of a giant, beautiful dance between the land, the sea, the sun, and the seasons. It is invisible but wind is a constant companion, shaping everything around us in ways we often overlook. We learnt about winds, currents and the seas movements. Winds don’t just push ships—they push water, too. When wind blows steadily over the ocean, it creates currents—like rivers flowing in the sea. These currents help distribute heat across the planet, support marine life, and even influence our climate. Almost all waves we see in the ocean are created by wind. Local winds create short, choppy waves, while distant storms generate long, rolling waves called swells. These swells can travel for thousands of kilometers, neatly lining up like soldiers by the time they reach our beaches. Surfers love them because these waves are powerful and beautifully formed.

And waves don’t just stop at the beach—they shape the land. Over thousands of years, waves, combined with rivers and wind, have sculpted India’s distinctive V-shaped coastline. It’s a system always searching for balance. The problem is, we’ve disturbed that balance. Take Pondicherry, for example. Before the harbor was built, sand flowed naturally along the coast, replenishing beaches as it went. But after construction, that flow was blocked. Beaches on one side grew, while others simply vanished. It’s not just harbors. Dams on rivers stop sand from reaching the sea, and sand mining for construction reduces it even further. Without that constant replenishment, the sea begins to eat away at the land. It’s like a broken machine. The natural system was always dynamic but stable. Now, we’ve jammed the gears, and the whole machine is off-balance. We’ve seen efforts to restore beaches in places like Pondicherry, but unless we maintain those efforts, nature won’t simply “fix itself.” The winds, the waves, the currents, the sand—they’re all part of a giant, interconnected system. It is beautiful. And it is fragile.

As Filio was concluding his crisp sharing of years of knowledge, the boat that was to take us on a short trip into the young neighbouring mangroves pulled up at our jetty, joining the parked kayaks and sailboats. With our life jackets on, we climbed aboard one by one, drifting past rows of fishing boats and the buzzing tourist carriers Filio had spoken about earlier. He oriented us and shared how it was possible to kayak or paddle on these waters just a few years ago.

The mangroves were beautiful—gentle, tender green against the dark grey of the polluted water. There are seven species here, with two dominant ones—silver-leaved and red-rooted varieties—Filio explained as he showed them to us, answering Lochan’s curious inquiry about the different trees absorbing nutrients from the city’s runoff. We moved through narrow openings and back again, our boatsman navigating the shallow waters with care. Every question we had was met with an answer, and we got to experience one of the hidden jewels of our city.

Eventually, we travelled toward the estuary, where backwaters merge with the salty expanse of the ocean, before looping back to where we had started. While the steady pace of the boat, the gentle wind, and the vibrant greenery were a treat to the senses, the sharp smell of fuel in the air was a sobering reminder of the other side of it all.

As we stepped off the boat, Filio pointed out how the tide had shifted since we began, tape measure in hand—making visible the subtle changes that usually go unnoticed, bringing us one step closer to observing the forces constantly shaping the world around us. We made our way back to land, welcomed by a delicious glass of fresh mango juice and more conversations before heading home equipped with essential nuggets of knowledge and fun facts about this living and ever changing bioregion we call home.

Now, each time the sea breeze brushes against my skin, I carry with me a bit more curiosity about its journey — with more attention, more gratitude, and a deeper understanding of the ocean’s constant, delicate dance towards balance.